The "Placebo" and "Nocebo" Phenomena - Their Impact on Treatment Outcomes

“Give someone who has faith in you a placebo and call it a hair growing pill, anti-nausea pill or whatever, and you will be amazed at how many respond to your therapy.” ~ Bernie Siegel

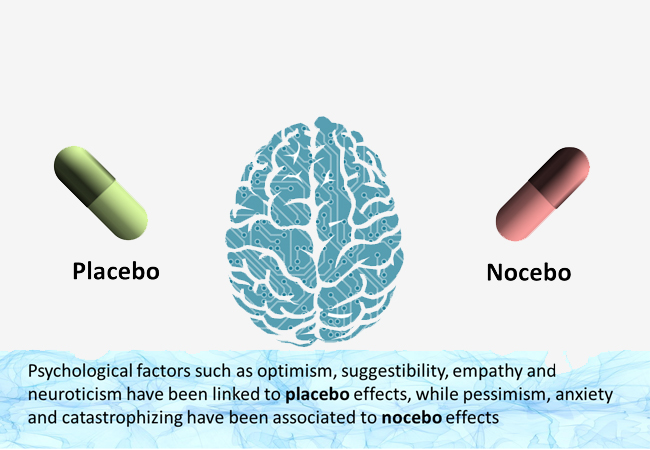

Placebo and Nocebo effects are psychobiological events imputable to the therapeutic context. Placebo is defined as an inert substance that provokes perceived benefits, whereas the term Nocebo is used when an inert substance causes perceived harm. Their major mechanisms are expectancy and classical conditioning. Placebo is used in several fields of medicine, as a diagnostic tool or to reduce drug dosage. Placebo/Nocebo effects are difficult to disentangle from the natural course of illness or the actual effects of a new drug in a clinical trial. There are known strategies to enhance clinical results by manipulating expectations and conditioning.

Placebo and Nocebo effects occur frequently and are clinically significant but are under recognized in clinical practice. Physicians should be able to recognize these phenomena and master tactics on how to manage these effects to enhance the quality of clinical practice.

The placebo effect has been studied extensively throughout history. The Nocebo effect, also called “the evil brother of the Placebo effect,” has been less studied, but in recent years has become a subject of growing interest. Both phenomena are composed of several intertwined biological and environmental mechanisms, displaying a complex interaction.

The term Nocebo comes from the Latin “to harm.” “The Nocebo effect is in fact an expectation about negative treatment outcomes,” explains health psychologist Andrea Evers of the University of Leiden in The Netherlands. Almost a polar opposite to the better-known placebo effect, it works through our negative assumptions and conditioning. “For example, there is a high risk that a cancer patient who has always experienced nausea after chemotherapy will expect this adverse side effect, and the anticipatory anxiety, (will then), produce the negative expectancy,” explains Evers. While the positive power of the placebo effect is well known, the negative impact of the Nocebo effect has been largely ignored.

Many strange and extreme medical events have been attributed to the Nocebo effect, including deaths. One reported case from the 1970s describes a cancer patient who died after being told he had three months to live, only for it to be discovered at autopsy that the stage of his cancer had been misdiagnosed and could not have been the cause of death.

The Nocebo effect may also be responsible for the phenomenon of mass psychogenic illness, where symptoms with no apparent cause rapidly spread through communities. The phenomenon could explain adverse reactions to Wi-Fi or wind turbines, which have been blamed for headaches, dizziness and fatigue.

Unfortunately, the Nocebo effect has a huge impact as the negative expectations tend to be formed much faster than positive expectations and this has an evolutionary reason – our bodies are programmed to protect us from adverse events.”

The effect can be seen regularly in clinical trials, says Evers. “You see the same number and type of side effects in patients who did not receive any intervention,” she says. “So by only reading the instruction letter the patients can experience the same type and number of side effects (as those who were given the active drug).”

Because people’s ideas about things like value and cost are often culturally determined, the Nocebo effect can vary across cultures and countries. What we are talking about is a set of beliefs and expectations that people are willing or not willing to accept, and this can be culturally determined. In general, it seems to be the case that the more trust and power people ascribe to a specific procedure, medical ritual, surgery or other things, the more Placebo and Nocebo effects are induced. Here is an example of pill size: “There seem to be some cultures who, on average, are more prone to believe that a small pill is really strong, and that is the reason why it is so small. In other cultures, a big pill is seen as more potent and these beliefs also shape Nocebo and Placebo responses.”

The Placebo and Nocebo effects can present clinicians with an ethical dilemma. Doctors have the duty, and patients have the right, to know what is happening to them. At the same time, being told what is happening to them might be counter-productive. But it turns out, ethics aside, lying about side effects is unlikely to be the right strategy in the long term. “We know warmth, empathy and trust always enhance the Placebo effect and make it stronger and reduce the Nocebo effect,’’ says Evers, who advocates open and transparent communication between clinicians and patients.

The framing of that communication seems to be the crucial part in terms of the balance of positive and negative messages, including making sure the patient understands the treatment rationale. Many times there is more attention to the negative part of the information, namely the description of side effects. We need to consider a good balance, with an empowerment of positive expectations and truthful information on side effects.

Evers also recommends that patients are made aware of the Nocebo effect: “You do not have to say the word “Nocebo” but, for example, explain that expectations can play a role in a positive and in a negative sense. In fact, there have been studies that have shown that even when patients know they have been prescribed a Placebo, it still works. “(This is) a very nice example that open, transparent relationships make it possible to make use of the Placebo and reduce the Nocebo effect,” she adds.

But Luana Colloca (associate professor in both the Department of Pain and Translation Symptom Science at the University of Maryland School of Nursing), suggests another ethical way of dealing with the Nocebo effect – she calls it “authorized concealment.” “We have to consider that not all patients are the same, there are patients who really want to be informed and to know any details, and patients who actually would prefer not to know,” she explains. Patients could consent to clinicians concealing all but potentially life-threatening side effects. Colloca estimates that 35–40% of patients would favor such an arrangement.

A crucial question for clinicians is whether a Nocebo response, once produced, can be reversed. The good news is that the answer seems to be yes. “The Nocebo effect could even be changed to a Placebo response,” says Evers. She has experimented with the idea by creating negative expectations in test participants and then attempting to reverse these expectations. Test subject were made to itch using an electrical stimulus and were told to associate a greater itch stimulus with a particular colored dot on a computer screen. Regardless of the actual stimulation intensity, participants felt a larger sensation (than the control group) when they saw the colored dot. But in a second experiment, the same participants were re-educated to reverse the color association. The researchers found that not only could they significantly reduce the Nocebo effect but participants actually felt reduced itch levels compared with a control group, effectively turning a Nocebo into a Placebo effect.

The potential for healthcare professionals to influence responses to medicines is becoming increasingly clear. Only giving the medication is not enough anymore because we know that the power of the brain may be modulating side effects. The right kinds of communication with patients have the potential to positively shape patient expectations and reduce side effects.

Clinically, Placebo and Nocebo effects are of major importance, being present in daily medical practice. The overall effect of a drug stems from its pharmaco – dynamic actions plus the psychological effect derived from the act of its administration. Although both Placebo and Nocebo have been widely studied, the full complexity of their mechanisms needs further definition. Thus, when correctly applied, there are a number of strategies that can improve responses and patients’ quality of life, maximizing Placebo and reducing Nocebo in clinical practice, and enhancing results in clinical trials. It underlines the impact of creating a good physician–patient relationship, increasing empathic attitudes, exposing information suitably, decreasing expectations of adverse effects, and promoting social contact between successfully treated patients.