"Why be broken, when you can be gold?" ~ Sarah Rees Brennan

The pandemic has shattered our World. So how do we heal these wounds? Should we expect, or even hope, for a return to what was? Just as a shattered bowl can never be fully mended - our bodies, our businesses, and our society can never be exactly what they were.

This impossibility of return should be cause for despair. But, paradoxically, it is a good thing that we cannot go back – and the ancient Japanese art of repairing broken pottery shows us why and how to work with failure. This ancient art – Kintsugi - can help us rebuild.

A beloved cup or bowl - perhaps a family heirloom - slips from our grasp and falls to the floor, shattering into pieces. A serious illness or injury rends our bodies and spirit. A pandemic forces businesses to furlough and lay-off employees, or close altogether. A nation in turmoil tears at the foundation that makes civil society possible.

The pandemic that struck this past winter shattered our collective vessel. The breaks happened fast and were painful to see and to experience. But just eighteen months later the first hints of gold are coming into view.

Obviously, we cannot and should not throw ourselves away when this happens. Instead, we can relish the blemishes and learn to turn these scars into art like - Kintsugi , an ancient Japanese practice that beautifies broken pottery.

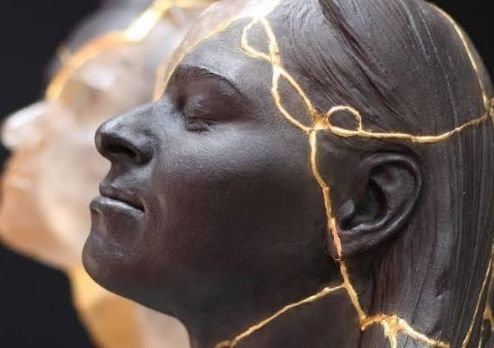

Kintsugi, or gold splicing, is a physical manifestation of resilience. Instead of discarding marred vessels, practitioners of the art repair broken items with a golden adhesive that enhances the break lines, making the piece unique. They call attention to the lines made by time and rough use; these are not a source of shame.

We are often relieved when other is truthful, we are afraid to expose ourselves. Psychologists call this distinction “beautiful mess effect.” We see other people’s honesty about their flaws as positive, but we consider admitting to our own failures much more problematic.

The Kintsugi approach instead makes the most of what already is, highlights the beauty of what we do have, flaws and all, rather than leaving us eternally grasping for more, different, other, better. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy explains, in Japanese Zen, the practitioner sits and works with what is.

In other words, the experiences you have, and the person you already are sufficient. You may, of course, occasionally chip and break and need repairs. And that is fine. But reality is the best and most abundant material on the planet, available to anyone, for free, and we can all use what we already have - including our flaws - to be beautiful. After all, our cracks are what give us character.

What patterns of gold will trace the fractures in our civil society? It is too soon to tell. The damage is still spreading, even as we gather up the pieces. But, as in so many other areas, people are coming together to bind up their collective wounds. From creative solutions for keeping food pantries stocked to neighborhood groups volunteering to pick up trash where sanitation budgets have been cut, there is hope that efforts to repair what has broken will ultimately lead to something even better.

Kintsugi sees this clearly. It acknowledges that while our breaks may be permanent, we should never be diminished by the scars that form. By covering them in gold that never fades, they become part of our history - a source of wisdom and a reminder of our strength.